It is in his capacity as editor of the magazine “Motor-Kritik” between 1928 and 1934 that Mr. Ganz took a keen interest in the development of a German “Volkswagen” and, together with other engineers like Professor Porsche, has greatly contributed to realizing this project.

Embassy of the Federal Republic Germany in Australia, 1965

With these words, the German authorities in 1965 argued why Dipl.-Ing. Josef Ganz (1898-1967) should receive the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. This attempt came almost three decades after the Jewish engineer Josef Ganz had escaped from Nazi-Germany, narrowly escaping assassination.

Josef Ganz was originally born in Budapest, on July 1, 1898. His father was the famous journalist and writer Dr. Hugo Markus Ganz, who originated from Germany and worked for the newspapers Frankfurter Zeitung and Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Although Josef Ganz, like his father, would later work as a journalist as well, he was especially fascinated by technology at an early age and was granted his first patent at the age of 12. After serving for the German navy in World War I, he enrolled into Mechanical Engineering studies, first in Austria and then from 1920 on in Germany.

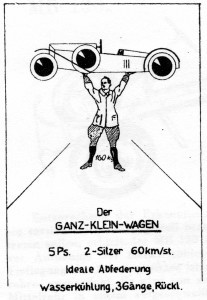

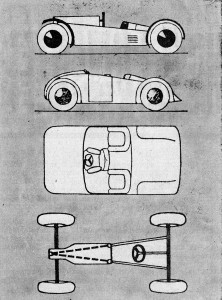

As a student, Josef Ganz became inspired by the idea to build a people’s car, or volkswagen, for the price of a motorcycle. In 1923 he made his first sketches for a small, lightweight, 4-wheeled car with a mid-mounted engine, independent all-round suspension, and a streamlined body. The design was inspired by the revolutionary Rumpler Tropfenwagen from 1921.

- Josef Ganz, photo taken from his motorcycle drivers license, 1920

- Prospectus Ganz-Klein-Wagen, 1923

- Prospectus Ganz-Klein-Wagen, 1923

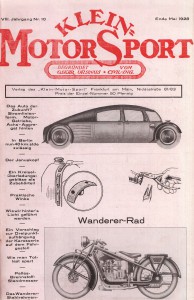

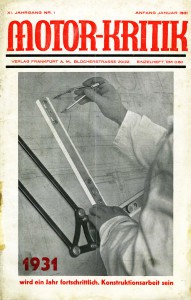

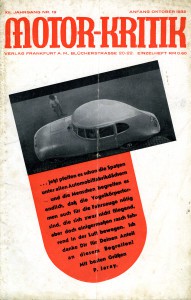

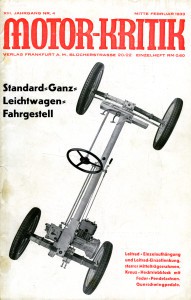

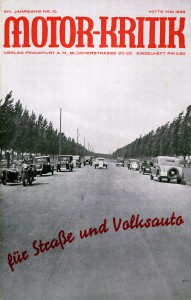

Since Josef Ganz lacked the funds to realize his ideas, he instead started writing about them for various motoring magazines. Shortly after his graduation as Diplom-Ingenieur in 1927, Ganz was assigned as the new editor-in-chief of Klein-Motor-Sport. He used this magazine, which he renamed Motor-Kritik in 1929, as a platform to give supportive but fierce criticism, fight against corruption in the automotive industry and press, and promote innovative technologies, including the idea for the Deutschen Volkswagen (German Volkswagen).

The automotive companies fought against Motor-Kritik with law-suits, slander campaigns and an advertising boycott. However, every new attempt for destruction only increased the publicity for the magazine and Josef Ganz firmly established himself as the leading independent automotive innovator in Germany.

- Klein-Motor-Sport issue 10, 1928, showing ‘The Car of the Future’

- Motor-Kritik issue 8, 1930, showing a modern front-wheel-driven car by Röhr

- Motor-Kritik issue 1, 1931, with a close-up of Josef Ganz designing the Ardie-Ganz prototype

In the summer of 1930, Josef Ganz built a first prototype of his Volkswagen at motorcycle manufacturer Ardie in Neurenberg. This small, lightweight car featured a central backbone chassis, independent all-round suspension with swinging rear half-axles, a mid-mounted engine, and a streamlined body. After the Ardie-Ganz prototype had proven itself, Josef Ganz built a second, more sturdy prototype when he was appointed as technical consultant at car manufacturer Adler in Frankfurt a.M. This prototype, completed in May 1931, was nicknamed Maikäfer (May Bug).

News about this revolutionary new model spread quickly through the industry, and many engineers tested the May Bug, including Ferdinand Porsche, Ferry Porsche and Adolf Rosenberger, before the Porsche design office started development of the Zündapp Type 12.

Besides at Adler, Josef Ganz was assigned as a consultant engineer at Daimler-Benz and BMW where he was involved in the development of the first models with independent wheel suspension: the highly successful Mercedes-Benz 170 and BMW AM1 (Automobilkonstruktion München 1). Furthermore, Josef Ganz managed to persuade director Wilhelm Kissel and technical director Hans Nibel of Daimler-Benz to develop new rear-engined models under his supervision. His brilliant engineering work and critical journalistic writings jump-started a revolution in the automotive industry to build affordable, lightweight, comfortable, safe and efficient cars.

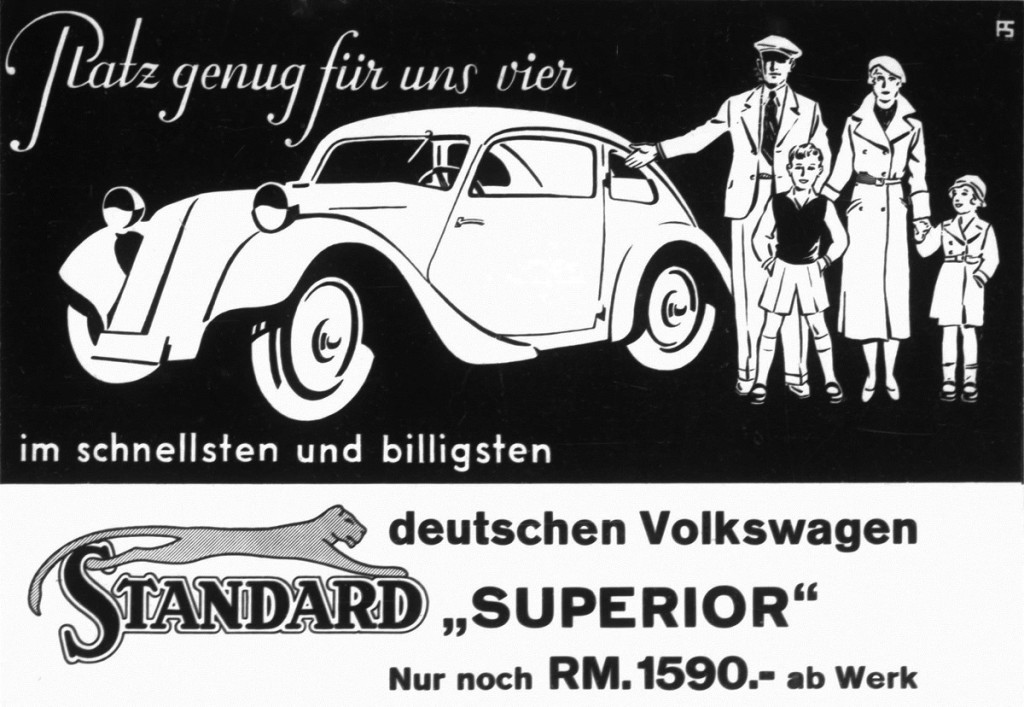

In February 1933, the Standard Fahrzeugfabrik from Ludwigsburg introduced their new Standard Superior model – a Volkswagen based on the patents of Josef Ganz – at the Berlin motor show IAMA. Adolf Hitler, who had become Chancellor of Germany just two weeks earlier, opened the motor show and expressed great interest in the design of the Standard Superior and its low selling price of only 1,590 Reichsmark.

While Ganz is thought to have been apolitical at the time, he initially supported the new government for its strong initiative to mobilize Germany by promoting small cars and building highways. His opponents, however, abused their influence with the new anti-Semitic government by making false accusations against him. Ironically, while many German car companies had started to adopt the progressive ideas promoted in Motor-Kritik, Josef Ganz was arrested by the Gestapo in May 1933 based on falsified charges of blackmail of the automotive industry. He was eventually released, but enemies in the Gestapo and the government systematically destroyed his career. Even his life was in danger.

- Motor-Kritik issue 19, 1932, showing a streamlined prototype by Paul Jaray

- Motor-Kritik issue 4, 1933, showing the chassis of the Standard Superior

- Motor-Kritik issue 10, 1933, dedicated to ‘roads and the people’s car’

This lead to his escape from Germany in June 1934 – the very month Adolf Hitler assigned Ferdinand Porsche to realize the prophecy of Josef Ganz: designing a mass-producible Volkswagen for a consumer price of 1,000 Reichsmark. The Standard Fahrzeugfabrik, which had recently released a new model with place for a family with two children, was now forbidden to use the name Volkswagen in its advertising.

Brochure for the Standard Superior, advertising it as ‘The fastest and cheapest German Volkswagen’, 1933

In 1935, Josef Ganz settled in Switzerland, where with government support he started a Swiss Volkswagen project. The first prototypes were constructed in 1937 and 1938 and plans were formed for mass-production inside a new factory. After the start of the Second World War, however, Josef Ganz was again under serious threat from the Gestapo and corrupt Swiss government officials who tried to claim the Swiss Volkswagen project as their own.

After the war, Josef Ganz, in a desperate attempt for justice, took his Swiss and German enemies to court. Numb from five years of highly complex court battles, Josef Ganz was forced to leave Switzerland in October 1950 and settled in Paris, France. He already had contacts in France, where he had worked on a new small car for Automobiles Julien, but could no longer compete with the German Volkswagen – which would soon be conquering the world in its millions.

In 1951, Josef Ganz decided to leave the old world behind and boarded an ocean liner to Australia. For some years he worked there for General Motors – Holden, but became almost bedridden after a series of heart attacks in the early 1960s. Despite some attempts to restore his name, it was too little too late. Josef Ganz died in obscurity in Australia in 1967, his legacy known and admired by all but his name forgotten. His desk lay full of evidence for his bizarre life story that he so desperately wanted to be told.